This morning I preached at Ravensworth Baptist Church. I think my weirdness showed. Normally it doesn't bother me but it has bothered me today, maybe because I want them to like me! Reign it in, lady! Sigh.

I thought I would share my sermon here with you all. I love to take a familiar text, in this case “The Parable of the Lost Sheep,” and dig into it until it no longer feels as familiar. It's fun!

So, without further ado….

Scripture Reading: Luke 15:1-7

Now all the tax collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

So he told them this parable: “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it? And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders and rejoices. And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my lost sheep.’ Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance.

Good Morning, Everyone. My name is Lauren Geraghty. I started attending RBC in November and became a member last month. I served in pastoral ministry until I left in September and now, I am figuring out what I want to do when I grow up…again! This morning, I feel a little hesitant but a lot honored to preach here at RBC, and even better, on one of my favorite passages, The Parable of The Lost Sheep.

Parables were the hallmark of Jesus’ teachings that he rarely offered explanations for. People would gather round to listen, and after the teaching, they would be challenged to wrestle with what was taught. Even the Gospel writers left these teachings open-ended, although, in today’s text, Luke offers his own interpretation that we will discuss.

Jesus left many of his teachings open-ended because he didn’t want to do the meaning-making for his followers. He trusted that if they leaned into the teaching, they would each hear a distinct message based on their own context and life experiences.

In her book, Short Stories by Jesus, Amy Jill Levine, a Jewish New Testament scholar, writes,

“What makes the parables mysterious, or difficult, is that they challenge us to look into the hidden aspects of our own values, our own lives. They bring to the surface unasked questions, and they reveal the answers we have always known, but refuse to acknowledge. Our reaction to them should be one of resistance rather than acceptance.

If we hear a parable and think, ‘I really like that’ or, worse, fail to take any challenge, we are not listening well enough. Such listening is not only a challenge; it is also an art, and this art has become lost. Too often, we settle for easy interpretations: We should be nice like the good samaritan; we will be forgiven, as was the prodigal son…If we stop with the easy lessons, good though they may be, we lose the way Jesus’ first followers would have heard the parables, and we lose the genius of Jesus’ teaching. Those followers, like Jesus himself, were Jews, and Jews knew the parables were more than children’s stories…They knew that parables and the tellers of parables were there to prompt them to see the world in a different way, to challenge, and at times to indict. We might be better off thinking less about what these parables ‘mean’ and more about what they can ‘do’: remind, provoke, refine, confront, and disturb.”

So here we are together, practicing the art of hearing what Jesus is still saying to us today even as this parable remains attached to its historical, 1st-century, Middle Eastern, Jewish setting.

I mentioned that Luke offers an interpretation of today’s parable in verse 7 (in italics, above). This is the interpretation that churches have traditionally taught. The shepherd is a metaphor for God. The sheep is a metaphor for Christ’s followers who have gone astray. The celebration at the end is a metaphor for the church. We sin. God forgives. It is important that we know this to be true. But if parables were meant to provoke, where would the provocation be?

Amy Jill Levine suggests that Luke’s interpretation might not be accurate. She points out that it is unlikely a first-century Jewish person would have understood a sheep as a repentant sinner. She jokes that sheep eat, sleep, and poop. They aren’t very smart. She suggests that instead of blaming the sheep for wandering off, we should blame the man who owns the sheep. Even though we have always assumed that it was a shepherd who retrieved the sheep, the Bible doesn’t say that. The Bible says that the sheep owner goes after the missing sheep. Shepherds were poor. But the sheep owner is wealthy, owning a heard of 100 sheep. Amy Jill Levine suggests a new title for this parable that would be closer to its earlier meaning. Instead of calling this parable “The Parable of the Lost Sheep,” it should be called, “The Man Who Lost His Sheep.”

Now that we have established that the sheep owner was wealthy, we might be surprised that he cared, or even noticed, that 1% of his large flock had been lost.

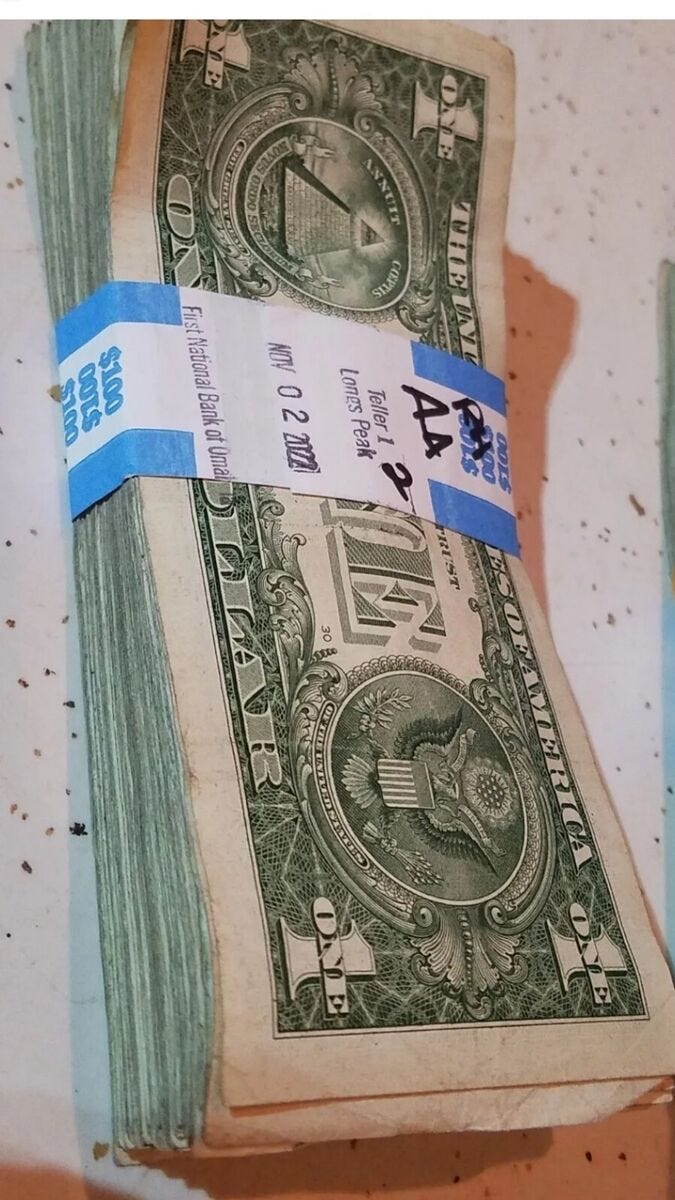

How much would you worry if you lost $1 from this stack?

Certainly, one missing sheep would not have impacted his bottom line. Nevertheless, when he noticed that one sheep was missing, he made sure to find it and bring it home. Why did he care about one sheep when he still had 99? We don’t really know because it doesn’t make any sense. What we do know is that he valued the individual life of each individual sheep just as much as he valued the collective flock, who continued to graze together. He miraculously noticed that his flock had shrunk by 1%. He left home to find the 1% and when he found that sheep, he put it on his shoulders and rejoiced.

After returning home, he invited his neighbors to celebrate with him. I’m sure his neighbors thought that was weird, and I bet the crowd who Jesus taught with this parable thought it was weird, too. This is where the story ends.

The final verse (7) is where Luke offers his interpretation. The one about the sheep being a repentant sinner.

Now that we know what we know, don’t you find it bizarre to believe that a sheep would ever be used as a metaphor for a repentant sinner? Sheep are not capable of introspection, self-reflection, or remorse. They are probably one of the most unintelligent and defenseless creatures in all of God’s creation. How could we be so heartless to blame an adorable and probably very fluffy sheep?

We are left to grapple…

I’ve preached on this parable before, and at that time, it challenged me to notice who was missing from our pews. From our leadership. From our choir. From our small groups. It prompted me to ask, “How did we lose them? Why did we not notice when they left? Did we even notice them when they were here? And instead of blaming them for leaving, it taught me that we should consider how we might have been responsible for their disappearance.

But today, I’ve discovered a new meaning from this familiar parable and want to share it with you.

A few minutes ago, I alluded to leaving pastoral ministry in September. And even though I knew that it had to happen, leaving the denomination that raised me and the calling I perceived was painful. So painful that after a while, I think I stopped believing that God actually cared about me. I didn’t feel mad at God. I didn’t blame God. I did not doubt God’s love for the world. But I just knew that God had stopped noticing me. I stopped hoping that God would have more ministry for me to do. I stopped believing that God would act in my life. I stopped expecting God to hear my cries, or even care about them if God did.

But in today’s parable, Jesus challenges my depressing beliefs. He teaches that God notices and cares for each one of us, even though we are just 1 of 8.062 billion people on this planet at this exact moment, not to mention all of the lives that have come before us and all of the lives that will come after us. Our lives are so miniscule in the grand scheme of things. That’s the POINT. Jesus taught that God notices and cares for each ONE of us as much as God cares for ALL of us.

The challenge does not stop there.

I said earlier that the sheep owner cared about that one sheep, even though it was such a small percentage of its flock and would not have impacted his bottom line. He cared about the sheep not because of what it was worth to him but because he cared about one life as much as he cared for the collective. It wasn’t about him as much as it was about the sheep. I once read that Americans (or maybe all of humanity) have a bad habit. I read that Americans tend to look away from something painful if it doesn’t impact us directly. We would rather pretend it's not real. This parable challenges that bad habit. It reminds us that Christians are never to look away. We must notice the pain around us, and we must look towards it. We can then tend to it, even when we could have turned away and continued to live our lives unaffected.

And so, this is a provocative and challenging parable, after all. It challenges us to reject the notion that our individual lives do not matter to God. It challenges us to receive God’s love. And it challenges us to notice and care for those who have never been noticed or cared for. Believing we matter and helping others feel the same. This parable is a call to action. A call to love and be loved. The greatest acts of resistance. So, let’s do it! May it be so. Amen.

My benediction is where I was weirdly awkward. I explained that my greatest spiritual task is being concise (joke, and I made the joke with 1,000 words. I had so many things I still wanted to say). Anyway.

For the benediction, I explained that my understanding of the church is not as a place we go. It is who we are. Wherever we go. There is God. And there is the church. When we gather together, we celebrate and encourage and strengthen one another. We practice loving and being loved, so that we can go out and do it all again, transforming the entire world (or at least our community) by the way we live and love.

I explained that I believe the love we receive from God can be thought of as the Christ who dwells within us. And when we leave worship, we will be challenged to allow the Christ who dwells within us to connect to the Christ who dwells within all others. What made me think of that is a piece of art a church member had drawn for our bulletin.

There are people we will not want to love. There are people we will not want to connect with. But the Christ who dwells within all of creation beckons to us from the heart of every person and all of creation. As we encounter God in those people and places, we experience what it is to be the beloved sheep. I mean, beloved children, of God.

Then I said …so, let's do that! Go in peace!

Here is the art from our church member, Ben, and his reflection.

“In reading over the scripture that inspired "Lost & Found" by Lisle Gwynn Garrity -- the parable of the Lost Sheep -- I was struck by just who it was that the Pharisees were objecting to Jesus spending time with: tax collectors. This was not tax collection as we know it now. It was not a civic duty that would improve the lives of ordinary people. This "taxation" was essentially wealth extraction by the Roman Empire: an extraction paid for most by the poorest Palestinian Jews, as the wealthy were able to skirt their fair share. Tax collectors were despised because they were collaborators with the Empire. They were traitors who made their living by, sometimes violently, taking even more than was owed to their masters. These are the lost sheep: the collaborators and traitors! Those who are selling out their neighbors for a few coins. I sympathize with the Pharisees: why waste time on saving these people? But in reality the tax collectors are in more danger than anyone: drowning their own humanity in an ocean of greed. For the good of all, Jesus sees that these Lost Sheep need to be rescued from themselves and brought back to the flock.”

Thanks for being here and taking the time to read my words. 🩶

LG

I don't think you got weird at all. This was a great sermon!